Riding Alone

The Cowboy, Community, and the Crisis of Modern Masculinity

Several years ago, my brother and I went on a John Wayne movie kick. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, McLintock!, The Searchers, Hondo, True Grit, The Comancheros, Rio Bravo—and to top it off, we endured the slog of How the West Was Won. I was fresh out of college, uncertain about my future and what kind of man I wanted to become. My brother was in the midst of those same questions. We spent that summer watching Wayne in all his glory—and somewhere between the gunfights and the dust, John Wayne’s cowboy gave me a sense of what it means to be a man. Well, not entirely. But he definitely made me feel it.

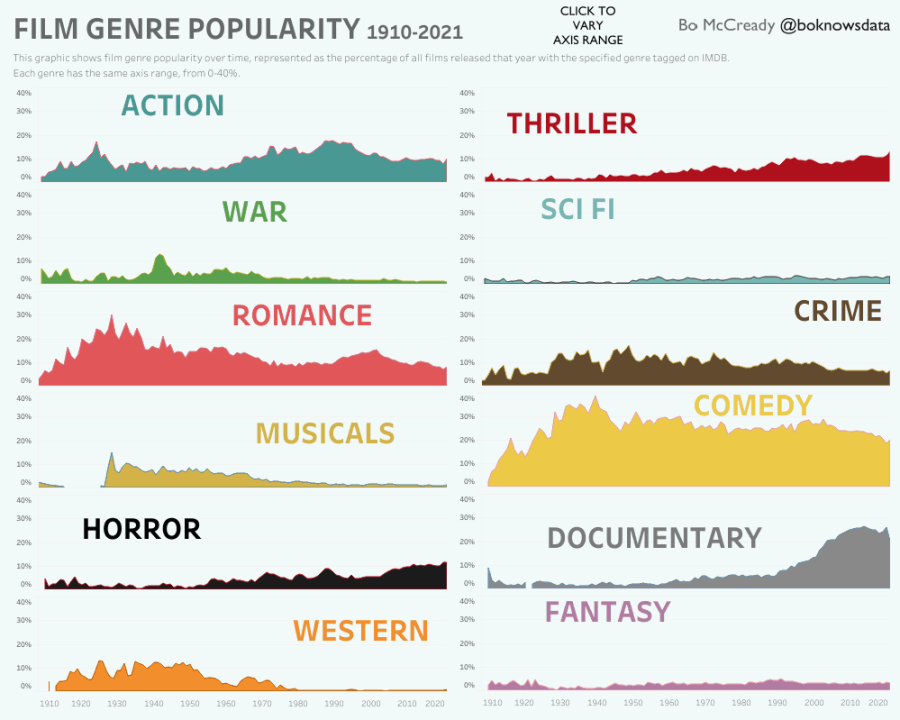

Sadly, the Western film genre has been in steep decline since the mid-20th century. While we can certainly list some good modern Westerns—or even Western-inspired characters like Cooper Howard in Fallout—there’s something to be said for the shifting film demographics. It isn’t a stretch to say that young men are the target audience for the Western genre and yet the film companies are no longer pouring money into the genre. Part of this is that young men, according to society, are the problem.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Take Kristin Kobes Du Mez for instance, who posits in her book Jesus and John Wayne that much of modern society’s ailments stem from the toxic embodiment of “John Wayne” white masculinity. I’m not convinced, to say the least. Instead, I see the rise and fall of the Western genre as telling the story of two clashing visions of masculinity and two clashing longings within men: the longing to be the lone hero and the longing for community.

Du Mez gets the diagnosis backward. Young men didn’t poison society with toxic John Wayne masculinity; it’s actually a mix of society abandoning young men and leaving them to become the lonely cowboy, and their willingness to step away from meaningful community. (Of course, in recent years we are seeing more young men come to church!) As the film industry shifted away from catering to young men, and as the culture stopped caring about their formation and struggles, young men were left without guidance. And in that vacuum, they defaulted to the only vision of masculinity still available to them: the rugged loner who needs no one.

The prophecy of the Western was a warning we ignored. The films we love in this genre were in our face telling us that young men need community, that they need a purpose and mission, and that if we don’t provide it they will find it on their own and in some of the worst places.

Two Cowboys, One Choice

The standard narrative when discussing the fall of the Western is that its death signifies the loss of rugged individualism in film. The Cowboy, in this thesis, was symbolic of the lone ranger. My thesis is a tad different: the Western showed us two types of cowboys—the lone ranger who needs no one, and the loyal brother who seeks community but struggles to achieve it (or chooses not to settle into the community). We, and when I say we I mean young men of which I am included, chose to emulate the loner. And the Western foretold what would happen when we did: a generation of isolated men desperately searching for the brotherhood they rejected.

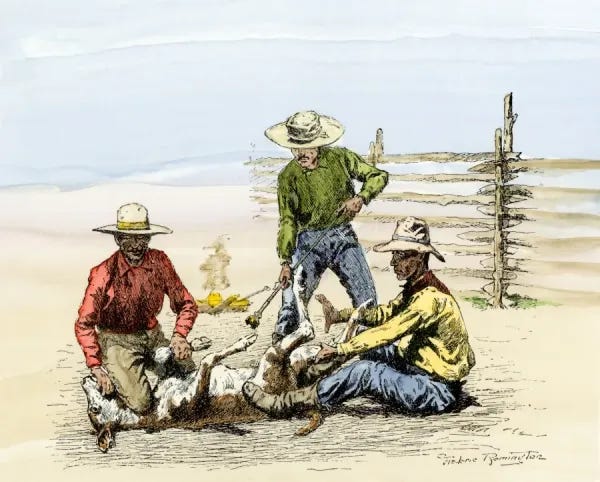

I’ve always been drawn to American Westerns. The untamed West—full of adventure, possibility, and danger. The lone cowboy, standing against the odds, fighting his way through whatever predicament came his way. Isn’t this what the cowboy life is all about? Perhaps not.

While John Wayne is the main character of his films, almost all of them involve working with others or banding together with a group to defend a town and protect the vulnerable. This speaks to the natural desire of men to work together, to protect and to lead. It’s instinctive. But there’s a tragedy: these men often cannot join the very communities they seek to defend. They ride into town, save the day, then ride out alone.

This is the image we remember. The loner. The individualist. The man who needs no one. (The Man Who Needs No One sounds like a killer Western title, right?)

But there was another cowboy in these films.

Consider Tombstone, the 1993 film that tells, loosely, the story of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday. Earp, Holliday, and Earp’s brothers Virgil and Morgan ride into a Mexican town run by outlaws known as “the Cowboys.” The Cowboys are symbolic of negative community—lawless drunkards who murder and take advantage of innocent people whenever they so desire. They wear red sashes as symbols of allegiance. Tombstone pushes back against the lone cowboy concept and instead posits a vision of friendship and community to combat this negative community: the Cowboys representing the wrong kind of brotherhood, Earp and his band of lawkeepers representing the right kind.

Unlike earlier iterations of cowboy films (Tombstone released in the 90s), Tombstone ends with a few counter-cultural themes. The first is Wyatt’s friendship with Doc Holliday. Val Kilmer portrays Holliday as awkward, eccentric—not the type of person who would make for a good close companion. And yet, Holliday says the reason he cares so much for Wyatt is simple: “He’s my friend.” Holliday shares a loyalty and camaraderie with Earp. This is further showcased when Earp visits Holliday on his deathbed. It’s hard not to see the loyalty of Earp, visiting his dying friend’s bedside. Holliday actually tells Earp to leave, but not out of a desire to be alone rather because he knows Earp needs something more.

The second counter-cowboy theme is Earp’s desire to be part of the community he just defended. Most cowboy films portray the central character as either disillusioned with the townspeople, unable to assimilate (”I’ve done too many bad things to be a part of normal life”), or simply the Lone Ranger needing no one but himself. Earp, however, desires to settle down. Holliday even chides him to settle down with the girl he loves—the theater actress Josephine Marcus.

This is the cowboy we forgot. The one who sought friendship and community. The one who found meaning not in isolation but in brotherhood. Certainly being a cowboy in the 19th century meant being alone—but it didn’t mean you couldn’t find meaningful community, even amongst other men.

Tombstone showed us in the ‘90s what we should have known all along: the lone cowboy was a myth. The real cowboy was a seeker—seeking friendship, purpose, and a community worth defending.

But by then, it was too late. We’d already chosen the loner.

The Death of the Genre

Pull up recent films or upcoming releases, and you’ll find new horror films, new action films, a few rom-coms sprinkled in for good measure. It’s rare you’ll see a new Western. This doesn’t mean they aren’t made—but the era of the cowboy is long gone.

What killed the cowboy? Perhaps it’s because the lone cowboy ideal was achieved—men became rugged individuals in a rugged individualist society. We got what we wanted. The prophecy fulfilled itself.

Another key factor in the death of the cowboy is the rise and dominance of comedy, horror, and romance. Cowboy films in the mid-20th century were fodder for young boys who often imagined what life was like struggling across the West. As America blossomed into an industrial force, it became increasingly harder to envision frontier life. Movies gave young boys a way to remember. In a culture built around community, the cowboy played to the longing for independence... for camaraderie... for adventure.

So what about comedy, horror, and romance? I’d like to posit that these genres indicate a shift in society itself.

The cowboy was growing unpopular due to shifting social concerns. The Vietnam War pumped carnage and death into living rooms across America. The Civil Rights movement brought turmoil to Southern cities. The assassination of JFK, as James Piereson argued in his book Camelot and the Cultural Revolution, shifted society toward a cult of progressivism—JFK was killed by right-wing thought, the narrative went, not by a disgruntled Communist upset with U.S. Cold War policy. All of this, and more, pushed Americans closer and closer to the TV, looking for a way to be distracted. Comedy gave laughs; horror gave fright; and romance gave the now-teenage cowboy fan food for his insatiable desire for love and companionship, while also inviting young women into the theater. Soon these three took over the film industry and the Cowboy was left to history, and the occasional remake of a classic (which are often pretty good).

In other words, the death of the genre cued the rise of an age of distraction.

The Lone Cowboy Prophecy Fulfilled

Young men today are facing a crisis of community. Fatherlessness, disaffection from local community, and being increasingly pulled online are all at play. There is a masculine crisis—one which Du Mez and others are only exacerbating by misdiagnosing the problem.

So who is the modern cowboy? The modern cowboy faces economic instability, social alienation, and a failure to launch. He’s mobile, never settling, and has no community. He’s angry at older generations and older generations are angry at him. He spends his time distracting himself from society’s problems, but more importantly, from his own problems. Video games, pornography, and online chats give him a semblance of meaning, but the meaning is actually a toxic pill slowly choking him out.

He is the lone cowboy we idolized. He’s isolated, adrift, and miserable. He achieved rugged individualism and it’s killing him.

Into this vacuum step the digital outlaws—men who promise what the modern cowboy desperately craves: purpose, brotherhood, and a villain to fight. Andrew Tate offers the image of strength, power, wealth, and control over one’s life, a return to dominance in a world that tells young men they’re toxic. Nick Fuentes offers tribal belonging and ideological warfare, a cause worth fighting for when everything else feels meaningless—meaning in the face of nihilism. These are the new sheriffs of the digital frontier, wearing red sashes of their own.

Recently, Andrew Tate, Nick Fuentes, Sneako, Tristan Tate, Clavicular, Myron, and Justin Waller arrived at a club playing Ye’s banned song “Heil Hitler.” This is the modern band of brothers—not the Hat Creek Cattle Company, not Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday defending Tombstone, but a grotesque parody of masculine community. They’ve banded together, certainly. They have loyalty, of a kind. They even have a shared cause—though it’s a bad one. But in the end it’s a community built on provocation, not protection.

They are the Cowboys—the outlaws in red sashes—not Wyatt Earp’s posse.

Furthermore, while the cowboy of the mid-20th century had a narrative role, the cowboy today has none. So he creates one. The town that needs saving? Gone. Now it’s about online loyalty—unwavering allegiance to a cause or position in the digital sphere. Tate’s followers defend his “Hustler’s University.” Fuentes’s “groypers” wage a full blown culture war in comment sections and constantly troll others for attention (need convincing? check out my piece on his friend Clavicular).

What about the clear villain? Also gone. The villain is no longer one person but whole groups of people—I can’t believe I’m writing this in 2026, but especially the Jews. This ambiguous mass of people and generalities makes the modern individualist cowboy skeptical of everything and everyone. The issue is always with everyone else, never with himself. His concerns are no longer local and present but global and digital. He gets involved in world events and thus loses his tie to reality and those around him. He has no town to defend—only abstract causes and digital battles.

Now, don’t read this as an endorsement. It’s not. However, Tate and Fuentes understand something the church has forgotten: young men are desperate for a narrative role. They’re desperate for a band of brothers. They’re desperate for a fight worth fighting. So these digital outlaws offer one. They offer a fight built on resentment, not godly righteousness. On power, not Christian service. On dominance, not Christ’s sacrifice.

The modern cowboy has found his gang. But like the red-sashed Cowboys of Tombstone, it’s the wrong one. It’s a lawless counterfeit. Men, we need to be like Wyatt Earp in this regard (of course not in his negative qualities, such as the fact that he has an affair). Trade the lone cowboy life for the true, meaningful life; the life of brotherhood around a noble, good, and true cause.

Riding Alone or Riding Together

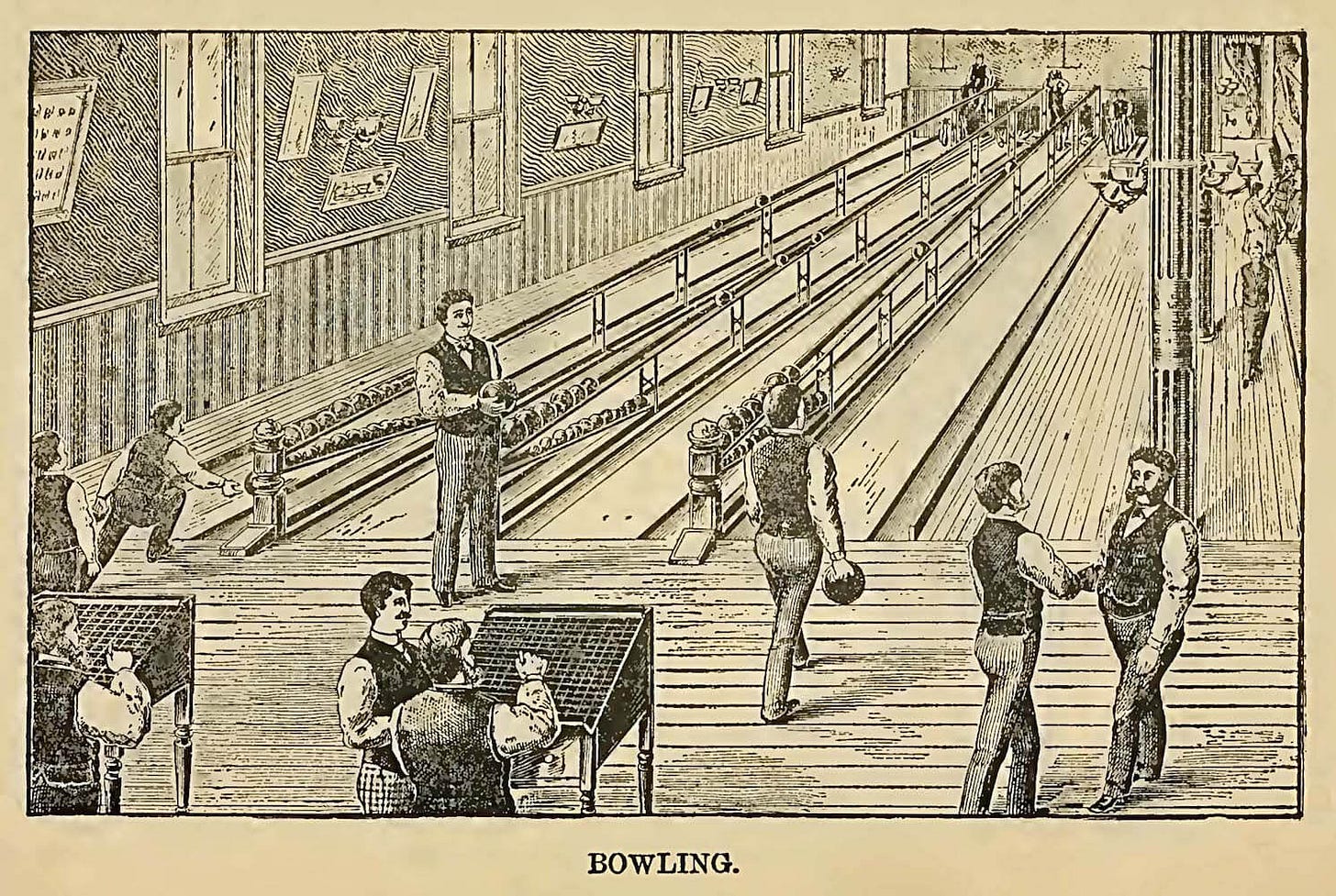

In his book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000), Robert Putnam explores the decrease of civic and communal social engagement among Americans. Putnam uses the illustration of bowling to make his point.

Starting in the 1960s and 70s, the number of people who bowled increased while the number of people who bowled in leagues decreased. Thus the act of bowling increased while the social act of bowling together decreased, according to Putnam.

Putnam is not merely waxing poetic about bowling, but is making a broader point: “People divorced from community, occupation, and association are first and foremost among the supporters of extremism.” What he means by “extremism” is up for discussion for sure—I’m sure Putnam would consider some typical Christian values to be extreme, for instance—but what isn’t up for discussion is that when we isolate ourselves, we risk moving into more extreme directions.

Putnam’s work was important in seeing the connection between social movements and social capital. By social capital, Putnam means social capital theory, which holds that social networks have innate value. The more we are isolated, the less we have access to basic functions of community. For instance, if your car breaks down in your driveway and you have never spoken to your neighbor, your relationship has very little purchasing weight—but one would hope the neighbor would help anyway, of course.

What is helpful for us here is that Putnam was correct that there are invisible social structures which uphold a healthy society. In the modern age, we have opted to ride alone—forsaking the capital of connection and loosening the bonds which make for a healthy society. It is little wonder we are seeing the rise of radical men and women pushing us further into the extremes. The modern cowboy is bowling alone. And Putnam warned us what happens when isolated individuals replace engaged communities: extremism fills the void.

Robert Nisbet, in his book The Social Philosophers, comments that one avenue of community is that of military camaraderie. When young men are together in the trenches, they no longer care about the cause—they aren’t ducking for cover in the face of artillery bombardments thinking, “I need to stay calm for the United States.” They’re thinking, “I need to stay calm for my friend next to me.”

When we’re in battle, or in the trenches, men tend to gather together and create a proverbial band of brothers. Of course, this can be a bad band as well—just look at the Cowboys from Tombstone, with their red sashes and outlaw allegiance. Putnam would recognize this tension immediately: social networks have value, but the kind of network matters. The Cowboy gang had social capital, which they used for destruction, not community building.

So what makes a good community? What makes a community that can push back and help us reclaim the right cowboy—the Tombstone kind, Wyatt Earp’s posse, not the outlaw Cowboys? Putnam gives us a framework: healthy communities require shared participation, face-to-face interaction, and networks of reciprocal relationships. Let me translate that into three practical steps.

First, a healthy community needs a common shared cause—what Putnam might call “collective efficacy.” Young men want to be part of something. The cowboy gave the young boy of the mid-20th century adventure. The young man today needs adventure too—real adventure, not digital simulation. If you’re a Christian, then there’s no better cause to live for than the Gospel message. Looking for risk and hardship? Go to a town, and share the message of redemption. Looking to be an outlier in the world? Share the biblical views on marriage, gender, and family. Jesus promised us that we would face hate for his namesake—what greater cause do we have than this one?

Second, a healthy community needs to be in real life. IRL—”in real life”—is something Gen Z uses online to express this sentiment. They desire to be real; they know nothing but the digital world and so try to escape its clutches. This is precisely Putnam’s point: the decline of face-to-face civic engagement has consequences. Digital connection is not the same as sitting across from someone at a bowling alley or around a campfire. This means intentionally setting up times in the real world to gather and adventure. Go for a hike. Have a bonfire. Go to a game. Go fishing. Take a trip into the wilderness. These aren’t trivial activities—they’re acts of resistance against the atomization and digitization of modern life. They’re the antidote to bowling alone.

Third, young men need a town to defend. This is where they get into trouble. They’re often defending the wrong town. Putnam warned that isolated people gravitate toward extremism—and we’re seeing this play out in real time. There certainly is a war against godly masculinity—the lines are drawn. But instead of defending some false image of masculinity posited by Andrew Tate and Nick Fuentes—who offer the outlaw Cowboys’ version of community—men need to band together and defend biblical masculinity. Jesus is the ultimate man—all of our efforts fall short if they go against his call to take up your cross and follow him. I also believe the church needs to step up and defend the eternal values that God has given us. It won’t make us popular, but to be truly human is to live with a desire to follow our Creator. Only by following in his path do we become truly what we were made to be.

I believe the church has failed to make this “town” a reality for some young men. There’s so much at stake here. Putnam documented the collapse of American community in 2000 and we’ve had over two decades to reverse course. Instead, we’ve doubled down on isolation. Either young men are retreating into the void or falling into false visions of masculinity—those predicated on power instead of godliness and truth. The modern cowboy is searching for what Wyatt Earp found in Tombstone: friendship, purpose, and a community worth defending. The question is whether the church will offer him that town—whether we’ll invite him to ride together instead of alone—or whether he’ll keep wandering the digital frontier in isolation, or worse, riding with the wrong community.